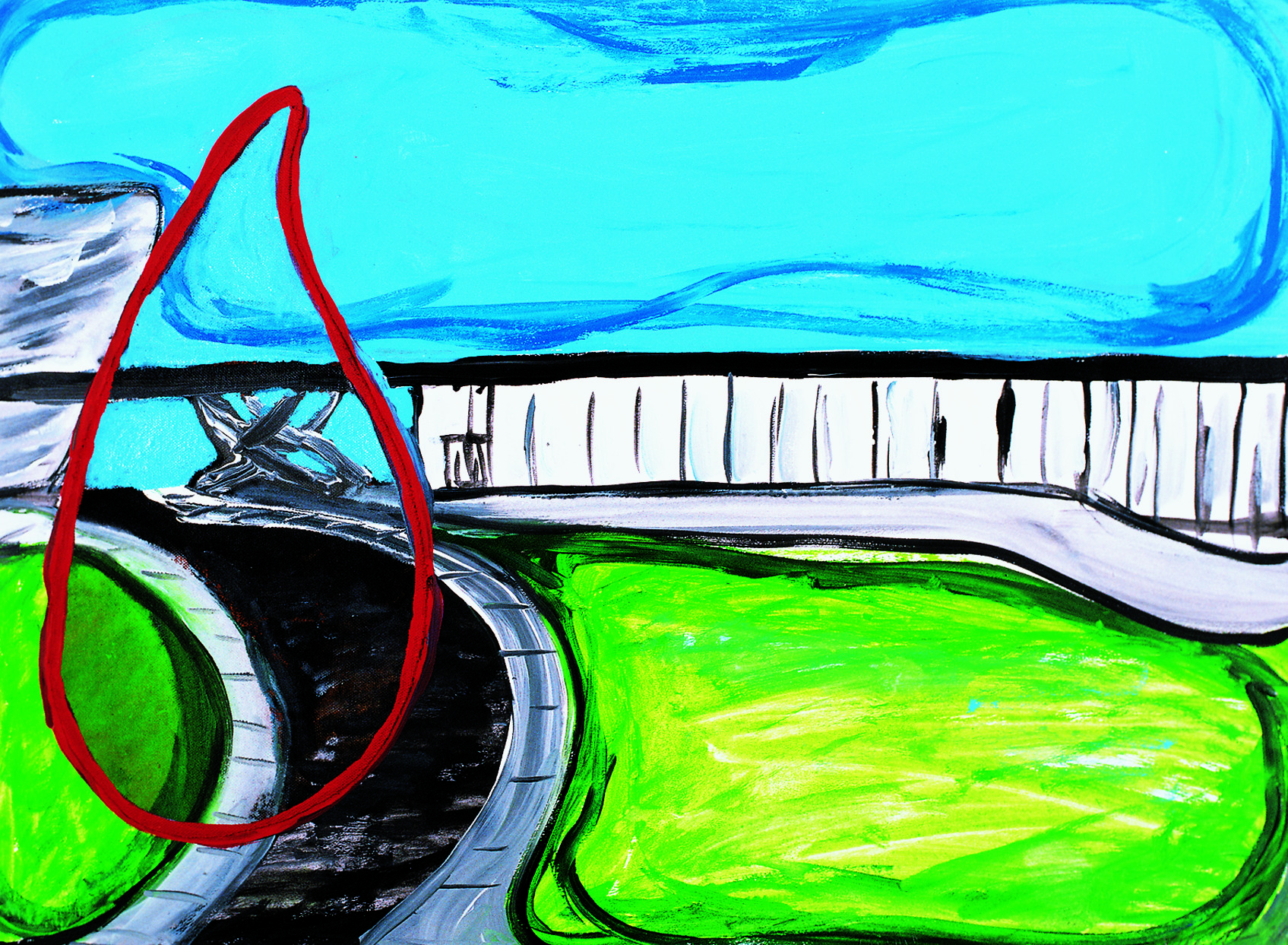

credits: Leda Catunda, MAM, 1998. Photo: Romulo Fialdini

mam são paulo: where the modern meets the contemporary

Over 77 years of existence, the collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo has undergone numerous transformations and reformulations, reflecting its significance for modern and contemporary art in Brazil. Since the late 1960s, the collection has gone through a continuous process of expansion and renewal. Thanks to generous donations from collectors, critics, art lovers, and the artists themselves, the MAM collection now comprises over 5,000 works. Most of them fall under the category of “contemporary art”, a term generally defined as covering work produced in the past 60 years. This group exceeds in quantity and volume the “modern art” pieces, which are typically associated with the early 20th-century modernist avant-garde movements.

The encounter between modern and contemporary art in the MAM collection provides a rich opportunity to reflect on the frequent debate surrounding how we define “modernity” and “contemporaneity”—and how these concepts relate to the kind of art that artists create. Traditional historical narratives often position modern and contemporary art at distinct points on a timeline, yet they do not always account for what truly distinguishes one from the other. This distinction becomes even more blurred, as styles and themes frequently converge and overlap—as is clearly reflected in the diverse works contained within the MAM collection.

While modern art emerged with the European avant-garde at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, in Brazil, modernist movements continued to evolve throughout much of the 20th century, developing at their own pace and in their own unique way. In fact, the emergence of contemporary art in Brazil can be traced to the evolution of one of the country’s last modernist avant-garde movements—Constructivism—by way of Concrete Art and the Neo-Concrete Movement. This transition was further shaped by the dialogue between these movements and dystopian avant-garde tendencies, such as Pop Art.

Modern art emerged as a break with the past and academic traditions. In turn, many view contemporary art as marking a break with modernist precepts, such as formalism and a reliance on medium specificity, embracing instead the possibilities of new media. The dream of revolution and the promise of freedom were characteristic of the modernist avant-gardes but have come to play a significantly less prominent role in the work of contemporary artists. The romantic idea of a better world—along with faith in reason and science—has increasingly given way to critical reflection on the unsustainability of modern life and the pursuit of personal micro-utopias.

The exhibition organizes works from different periods of recent Brazilian art history into six thematic units: “Nature: The End of Representation”, “Urban Environment: The Habitat of Modernity”, “Bodies: The Politics of Relations”, “Forms of Building and Breaking”, “Fragments, Gestures, and Abstractions”, and “Media: Updated Traditions”. These groupings bring together works from diverse contexts and time periods, highlighting how recurring themes of modernity persist in contemporary art as reflections of our lived experience—often blurring the boundaries between eras. Within each unit, works by artists who are still active today are juxtaposed with those of the modernist avant-garde movements. In terms of visual language, technique and conceptual approaches, these works reframe issues first raised by industrial modernity that have been further exacerbated by contemporary technological advances. Recognizing the ongoing relevance of these artistic perspectives provides a critical tool crucial for a society that needs to navigate the dystopian challenges of the present world.

The MAM’s current collection raises important cultural, social and historical questions. What is the relationship between the ‘modern’ and the ‘contemporary’? In what ways do they differ and in what ways are they similar? How do these distinctions shape the way we create cultural artefacts and narrate history? Are they merely differences of period and style? While there are historical and theoretical differences that certainly warrant extensive discussion, can we truly, with any meaningful degree of precision, define where—in terms of time or visual language—modern art ends and contemporary art begins? And how does this relate to our perception of historical time and of the time we experience? Rather than providing definitive answers, this exhibition seeks to foster diverse perspectives, inviting visitors to engage in these questions and be surprised by the insights that art can awaken—regardless of the time in which it was created.

Curators

Cauê Alves

Gabriela Gotoda

modern and contemporary art in focus

The Fiesp Cultural Center’s Art Gallery is proud to host MAM São Paulo: Where the Modern Meets the Contemporary. This exhibition brings together iconic figures from art history to encourage dialogue and reflection on the features that mark the transition from modern to contemporary art, taking as its starting point the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo (MAM São Paulo).

The exhibition invites visitors to explore and reflect on the cultural contexts and historical events that shaped the creation of these works of art, and the lasting impact they continue to have today.

SESI-SP is an institution dedicated to education in the broadest sense, with culture playing a prominent role. All of its initiatives and projects aim to educate new audiences about art, promote and provide free access to cultural experiences, and foster the creative economy in Brazil.

SESI-SP

nature: the end of representation

For much of history, the faithful representation of nature was regarded as the unquestioned purpose of art. The modernist avant-garde and contemporary artists, however, rejected this prescription and proposed new ways of imagining and reflecting on our relationship with the natural world and its elements. Victor Brecheret and John Graz, for instance, depict figures using compact volumes and drawings that evoke natural forms without imitation, preferring instead to highlight their most significant features. Siron Franco’s sculpture perfectly replicates all the physical aspects of a cocoon, and yet the similarity is undermined by the unnaturally exaggerated size. Raoul Dufy’s painting and the prints of Oswaldo Goeldi and Carlos Vergara present highly expressive images. In Dufy’s work, vibrant brushstrokes give form and movement to a static vase of flowers. In Goeldi’s woodcuts, the lines and patches of color create an air of mystery and melancholy, while Vergara’s use of iron oxide to print an image of a fish cannot fail to remind us of the insalubrious environmental conditions under which many such creatures are currently forced to live. Haruka Kojin and Ione Saldanha combine synthetic colors with the aesthetic power of natural elements to create abstract works. Similarly, Leonilson’s painting appropriates the physical characteristics of a river as metaphors for emotional states, transforming the objectivity of nature into a conduit for subjectivity. (G.G.)

urban environment: the habitat of modernity

The notion of modernity has for a long time been closely tied, from a historical and cultural perspective, to urban environments and industrialization. However, many modern paintings of the 1930s and 1940s—such as those of Di Cavalcanti, Francisco Rebolo, Tarsila do Amaral and José Antonio da Silva—depict suburban areas and the outskirts of cities at a time when urban development was still in its very early stages. Instead of city life and landscapes, with towering buildings and bridges, Tarsila do Amaral presents rural farm scenes with small houses, trees, and cacti. José Antonio da Silva portrays villages that are still quite undeveloped, where country markets, horse-drawn transport, and a slower pace of life reveal a world that is a far cry from the frenetic rhythm of the modern metropolis. During this period, many modernist painters adopted traditional forms, favoring rustic imagery as a more accurate reflection of the Brazilian culture of the time. By contrast, contemporary artists such as Leda Catunda, Shirley Paes Leme, and André Komatsu engage directly with the urban environment. Catunda depicts the glass façade of the MAM building in Ibirapuera Park, while Paes Leme repurposes an air-conditioner filter to expose São Paulo’s air pollution. Komatsu, in turn, presents broken glass and shattered windows patched up with chipboard. The works of these artists reveal a city that, despite its green spaces for leisure and its cultural institutions, remains an inhospitable and violent environment. (C.A.)

bodies: the politics of relation

The representation of the human body in modern and contemporary art reveals that the relationships that we establish through it are replete with power dynamics. Some of these relations arise naturally, as in the case of emotional and family ties, while others are determined by specific contexts and conditions that dictate the proximity or distance of bodies in dynamic situations. In Cândido Portinari’s prints—created to illustrate a special edition of Machado de Assis’s Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas—characters from the novel are depicted in expressive gestures, clothing, and interactions that convey their relationships, even without textual references. Heitor dos Prazeres’s painting and Lívio Abramo’s watercolors capture the energy of dance in dynamic images of posed bodies and billowing skirts. The works of Ismael Nery, Anna Maria Maiolino, Antônio Henrique Amaral, and Marco Paulo Rolla explore bodily intimacy from various perspectives, some more symbolic, others more literal. Meanwhile, Rubens Gerchman and Claudio Tozzi introduce the theme of social and political order, their works marked by the national context of the military dictatorship under which they were created. Flávio de Carvalho and Samson Flexor’s portraits address issues relating to the representation of identity, employing Cubist fragmentation as a visual strategy to generate subjectivity. By contrast, Letícia Parente, Ana Maria Tavares, and Tunga omit the body entirely, suggesting its presence when we reflect on the function of the objects portrayed. (G.G.)

fragments, gestures, and abstractions

Modern art is often associated with abstraction, which is also a common feature of the work of contemporary artists. The origins of abstraction lie in the fragmentation of nature, or rather in magnifying a fragment to the point where it becomes detached from its original reference. Aldo Bonadei’s paintings, for instance, do not depict reality by way of point-by-point representation; instead, figurative elements from the still-life tradition are juxtaposed with geometrical abstraction. Similarly, Antônio Henrique Amaral isolates a small patch of a banana cluster—an emblem of Brazilian identity, shaped by economic and cultural associations, from Carmen Miranda to Tropicalism—to create a series of abstract green and yellow strips. Sandra Cinto’s delicate pen-and-ink drawings exist in a liminal space between figuration and abstraction, a dialogue that MAM has been engaged in since it was founded in the 1940s. Beatriz Milhazes, in turn, employs vivid colors and collage, combining geometrical patterns, circles, mandalas, and floral motifs. Artists such as Flávio Shiró, Samson Flexor, and Yves Klein transform gesture into painting, using brushes, paint, and even the artist’s or model’s own body as a medium of expression. (C.A.)

forms of building and breaking

The constructivist movement of the European modernist avant-garde took root in Brazil from the late 1940s onward. Artists associated with Concrete Art, such as Geraldo de Barros, Hércules Barsotti, and Luiz Sacilotto, explored geometric forms and abandoned any lingering traces of representation that abstract art had retained. Their work embodied a utopian vision in which the transformation of art and visuality was seen as capable of leading to broader changes in the world. Samson Flexor—along with Hélio Oiticica, who would later take a very different artistic path—was also closely aligned with Constructivist painting in the 1950s. Meanwhile, artists such as Alfredo Volpi, a staunch advocate of craftsmanship and folk art, arrived at his own distinct form of Constructivism through a highly personal approach. Mira Schendel and Sergio Camargo, though never formally affiliated with any avant-garde grouping, both engaged in their own fashion with fundamental geometric forms, exploring empty space and simple shapes in ways that broke with tradition and opened up new artistic possibilities. In printmaking, Arthur Luiz Piza addressed constructivist themes but introduced an element of instability—his rigid geometric patterns subtly hinting at disorder and chaos. Cildo Meireles, in his three-dimensional works, subverts the logic of constructivist equilibrium by arranging tables and chairs of various sizes in such a way that smaller objects nestle under larger ones, paradoxically supporting heavier structures and prompting reflection on hierarchies and power dynamics. (C.A.)

media: updated traditions

Contemporary art is often defined by its embrace of new media and unconventional artistic languages. However, while technologies such as photography and video are frequently associated with contemporary artists, these were already being explored by artists of the modernist avant-garde. Likewise, contemporary artists continue to engage with traditional media and forms of expression, such as newspapers, printed pages, and drawings, integrating these into their visual and conceptual work. Alberto da Veiga Guignard’s photomontages were among the earliest fine art experiments to use photography in Brazil, displaying affinities with Surrealism on account of their dreamlike qualities and symbolic imagery. Antonio Dias’s The Illustration of Art video series was one of the first works of videoart produced in Brazil. The series uses homemade video recordings to question how we illustrate or conceptualize art. León Ferrari, Franklin Cassaro, and Antonio Manuel employ the materiality of newspaper as a means of engaging the viewer conceptually, both through expectations regarding the function of their chosen medium and by inviting various forms of interaction with the shapes and volumes created. Similarly, the works of Artur Barrio and Rodrigo Matheus use decontextualized elements, arranged in compositions that make up material “drawings” and renew the formal and conceptual possibilities of this most ancient of artforms. (G.G.)